Best Pharmacy Course 6 months

Pharmacy Course 6 Months. Mobile Phone Number 01797522136, 01987073965. 6 Month Pharmacy Course Contains 5 Subjects. Total Exam Marks 500. Weekly Class 3 Hours. If you want to complete our course please contact with us, Mobile No. 01987-073965, 01797-522136. HRTD Medical Institute, Abdul Ali Madbor Mansion, Section-6, Block-Kha, Road-1, Plot-11, Mirpur-10 Golchattar, Metro Rail Piller No. 249, Dhaka-1216.

Location Address for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

HRTD Medical Institute, located at:

Section-6, Block-Kha, Road-1, Plot-11,

Metro Rail Pillar-249, Folpotti Mosque Lane,

Mirpur-10, Dhaka-1216.

Contact: 01797522136, 01987073965, 01784572173

Subjects for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

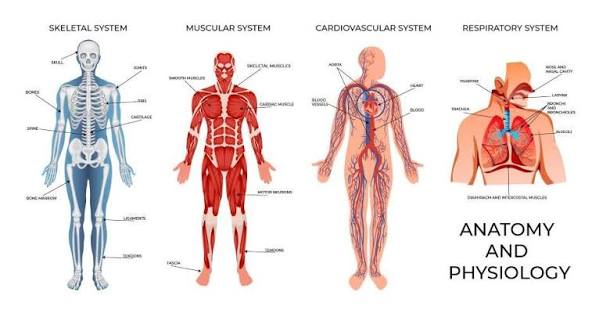

- Human Anatomy and Physiology

- General Chemistry and Pharmacology-1

- First Aid and Study of OTC Drugs

- Pharmacology-2

- Microbiology and Antimicrobial Drugs

Practical Classes for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

Heartbeat, Heart Rate, Tachycardia, Bradycardia, Pulse, Pulse Rate, Weak Pulse, Strong Pulse, Blood Pressure, Systolic Blood Pressure, Diastolic Blood Pressure, Pulse Pressure, Mean Blood Pressure, Hypertension, Hypotension, First Aid of Hypertension Emergency, First Aid of Shock, Cleaning, Dressing, Bandaging, Injection Pushing, IM Injection Pushing, IV Injection Pushing, SC Injection Pushing, Saline Pushing, Respiratory Meter, Inhaler, Rotahaler, Nebulizer, Oxygen Cyllinder, Blood Grouping, Blood Glucose, Diabetes Checkup, etc.

Teachers for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

- Dr. Sakulur Rahman, MBBS, CCD

- Dr. Sanjana, BDS, MPH

- Dr. Disha, MBBS

- Dr. Tisha, MBBS

- Dr. Mahinul, MBBS

- Dr. Juthi, BDS

Hostel and Meal Facilities

Human Anatomy for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

View all

Human anatomy is the scientific study of the body’s structures, from large parts (gross anatomy) to microscopic cells (histology), organizing them into systems like skeletal, nervous, and digestive, helping us understand what the body is and how its parts work together, crucial for medicine and biology. It’s studied regionally (e.g., head, limbs) or systemically, focusing on function (physiology).

Key Aspects of Human Anatomy

- Study of Structure: Anatomy defines the location, composition, and relationships of body parts, while physiology explains their functions.

- Levels of Organization: From cells and tissues to organs, organ systems, and the whole organism.

- Major Systems: The body comprises 11 major systems, including:

- Skeletal: Bones, cartilage.

- Muscular: Muscles, tendons.

- Nervous: Brain, spinal cord, nerves.

- Cardiovascular (Circulatory): Heart, blood vessels.

- Digestive: Stomach, intestines, liver.

- Respiratory: Lungs, airways.

- Endocrine: Glands (hormones).

- Integumentary: Skin, hair, nails.

- Urinary: Kidneys, bladder.

- Lymphatic/Immune: Lymph nodes, spleen, immune cells.

- Reproductive: Male & Female organs.

- Study Approaches:

- Gross Anatomy: Structures visible to the naked eye (e.g., dissection).

- Microscopic Anatomy (Histology): Study of tissues with microscopes.

- Regional Anatomy: Studying body areas (head, torso, limbs).

- Systemic Anatomy: Studying specific systems (nervous, skeletal).

Human Physiology

Human physiology is the scientific study of how the human body’s cells, tissues, organs, and systems work and interact, from molecular mechanisms to organ-level functions, all aimed at maintaining a stable internal environment (homeostasis) through complex physical and biochemical processes to support life. It explains the “how” and “why” of normal bodily functions, like breathing, digestion, and movement, forming the foundation of medicine by showing how the body responds to health, stress, and disease.

Core Concepts

- Homeostasis: The body’s ability to maintain stable internal conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, blood sugar) despite external changes, a central theme in physiology.

- Levels of Organization: It examines functions from the smallest (molecules, cells) to the largest (organ systems, the whole organism).

- Interconnected Systems: Focuses on how systems like the nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems work together.

Key Areas of Study

- Cellular Physiology: How individual cells perform basic functions like energy production and reproduction.

- Organ System Physiology: How systems like the digestive, urinary, and circulatory systems carry out complex tasks.

- Exercise Physiology: How the body adapts to physical activity.

- Neurophysiology: How the nervous system transmits signals.

General Chemistry

General Chemistry is the foundational study of matter, energy, and their interactions, covering core concepts like atomic structure, bonding, the periodic table, chemical reactions, stoichiometry, states of matter, thermodynamics, kinetics, and equilibrium, typically serving as an introductory, year-long university course for science majors, often with a lab component to explore experiments. It builds essential skills for advanced chemistry and other STEM fields by explaining how atoms form molecules and how these interact.

Key Topics Covered

- Fundamentals: Matter, energy, units, scientific measurement.

- Atomic Theory: Subatomic particles, electron configurations, quantum models.

- Bonding: Ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, molecular geometry.

- Reactions: Balancing equations, stoichiometry, types of reactions (redox, acid-base).

- States of Matter: Properties and behavior of gases, liquids, and solids.

- Thermodynamics & Kinetics: Energy changes, reaction rates, and equilibrium.

- Solutions: Concentration, solubility, colligative properties.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology is the scientific study of drugs and their effects on living organisms, covering how substances interact with the body, their uses, mechanisms, and toxicity, including understanding how the body handles drugs (pharmacokinetics: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) and how drugs affect the body (pharmacodynamics). It’s a crucial field for developing new medicines, ensuring drug safety, and personalizing treatments, bridging chemistry, biology, and medicine.

Key Areas of Study

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): What the body does to the drug (ADME).

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): What the drug does to the body (molecular targets, effects).

- Drug Development: Designing, testing, and creating new therapies.

- Toxicology: Studying adverse effects and toxicity.

- Pharmacogenetics/Genomics: How genes influence drug response.

What Pharmacologists Do

- Investigate how medicines work at cellular and molecular levels.

- Determine safe dosages and administration methods.

- Research biological processes to find new drug targets.

- Work in research labs, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare.

First aid

First aid is the immediate, basic care given to someone with an injury or sudden illness to preserve life, prevent worsening, and promote recovery until professional medical help arrives, ranging from cleaning a minor cut to performing CPR for a severe emergency. Key steps include ensuring scene safety, calling emergency services (like 911), assessing the victim, providing care (like bandaging or rescue breaths), offering comfort, and handing over to paramedics.

Core Principles

- Preserve Life: Save lives by managing severe bleeding or airway obstructions.

- Prevent Worsening: Stop a minor issue from becoming a major one.

- Promote Recovery: Help the person heal faster.

Key Steps in an Emergency

- Ensure Safety: Check the scene for danger to yourself or the victim.

- Call for Help: Activate emergency services (e.g., 911) immediately for serious situations.

- Assess the Situation: Check responsiveness (tap and shout) and look for medical ID.

- Provide Care:

- For choking: Give back blows and abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver).

- For no breathing/pulse: Start CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) if trained.

- For minor cuts/burns: Clean and bandage.

- Provide Comfort: Reassure the person and keep them calm.

- Handover: Provide details to arriving medical professionals

Microbiology

Microbiology is the scientific study of microscopic organisms (microbes) like bacteria, viruses, archaea, fungi, and protozoa, exploring their structure, function, evolution, and interactions, crucial for understanding disease, health, ecology, and biotechnology. These tiny life forms, often invisible to the naked eye, are studied using microscopes and culturing, with branches including medical, environmental, and industrial microbiology.

Key Aspects of Microbiology:

- Subjects: Bacteria, viruses, fungi (yeasts, molds), archaea, algae, and protozoa.

- Scope: Covers biochemistry, physiology, genetics, ecology, and evolution of microbes.

- Importance: Essential for medicine (pathogens, antibiotics), food production, environmental processes, and biotechnology.

Major Branches:

- Medical Microbiology: Focuses on disease-causing microbes (pathogens).

- Bacteriology: Study of bacteria.

- Virology: Study of viruses.

- Mycology: Study of fungi.

- Immunology: Study of the immune system’s response to microbes.

- Environmental Microbiology: Studies microbes in ecosystems, soil, and water.

Techniques:

Genetic Techniques: Gene editing (like CRISPR) and synthetic biology to understand and engineer microbes.

Microscopy: Using microscopes to visualize microbes.

Culture: Growing microbes in labs to study them.

Heartbeat Practical for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

A heartbeat is the rhythmic contraction and relaxation of the heart, driven by electrical signals, pumping blood through the body, with phases of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole) that typically occur 60-100 times a minute at rest, moving oxygenated blood to the body and deoxygenated blood to the lungs. It’s a vital function controlled by the heart’s natural pacemaker, the SA node, ensuring continuous circulation.

How it works:

- Electrical Signal: An impulse starts at the sinoatrial (SA) node, your heart’s natural pacemaker.

- Atrial Contraction (Diastole begins): The signal spreads, causing the atria (upper chambers) to squeeze and push blood into the ventricles (lower chambers).

- Ventricular Contraction (Systole): The signal moves to the ventricles, making them contract forcefully.

- Pumping Action: The right ventricle sends blood to the lungs, while the left ventricle pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body.

- Relaxation (Diastole): The heart relaxes, filling with blood again, restarting the cycle.

Key Terms:

- Systole: The contraction phase (pumping).

- Diastole: The relaxation phase (filling).

- Pulse: The rate at which your heart beats, usually 60-100 bpm at rest, increasing with activity.

OTC Drugs

OTC (Over-the-Counter) drugs are medicines available for purchase without a doctor’s prescription, used for common ailments like pain, colds, allergies, and minor skin issues, but they still carry risks and should be used carefully, following label instructions for proper dosage, side effects, and interactions. They treat minor health problems and include familiar names like acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil) for pain, antihistamines (Benadryl) for allergies, and hydrocortisone for skin conditions.

What they are

- Medicines sold directly to consumers without a prescription.

- Used for mild health problems such as headaches, fever, congestion, minor aches, and upset stomachs.

Common types & examples

- Pain/Fever: Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), Acetaminophen (Tylenol).

- Allergies: Antihistamines like Loratadine (Claritin), Cetirizine (Zyrtec), Diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

- Colds/Congestion: Decongestants like Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed).

- Skin Issues: Hydrocortisone creams for eczema, antifungal creams for athlete’s foot.

Important considerations

- Safety: OTC drugs can have side effects and interactions, just like prescription drugs, and misuse can cause serious problems.

- Proper Use: Always read and follow the label instructions for dosage and frequency.

- When to See a Doctor: Use common sense to know when symptoms are severe enough (like a persistent headache or severe heartburn) to warrant a doctor’s visit, as some symptoms can signal serious conditions.

- Pharmacy Advice: Speak with a pharmacist if you’re unsure if an OTC medicine is right for you.

Antimicrobial drugs

Antimicrobial drugs are medicines that fight infections from microbes like bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, working by killing the germs (bactericidal/fungicidal) or stopping them from multiplying (bacteriostatic/fungistatic). They’re categorized by target (antibiotics for bacteria, antivirals for viruses, antifungals for fungi, antiparasitics for parasites) and spectrum (broad-spectrum for many microbes or narrow-spectrum for specific ones). These drugs are crucial for treating infections in humans, animals, and plants, but overuse leads to antimicrobial resistance, where microbes evolve to resist the drugs.

Types of Antimicrobial Drugs

- Antibiotics: Target bacteria, like penicillin (narrow-spectrum) or broad-spectrum types.

- Antivirals: Combat viruses, like baloxavir (Xofluza).

- Antifungals: Treat fungal infections (e.g., azoles).

- Antiparasitics: Fight parasites causing diseases like malaria (e.g., metronidazole, albendazole).

How They Work (Mechanisms)

- Cell Wall Disruption: Some antibiotics stop bacteria from building their cell walls.

- Metabolic Pathway Interference: Drugs like sulfa drugs block essential processes, such as folic acid synthesis, needed for microbial growth.

- Protein/Nucleic Acid Inhibition: Disrupting the production of proteins or DNA/RNA.

Heart Rate Practical for Pharmacy Course 6 Months

Heart rate is how many times your heart beats per minute (bpm), with a normal resting rate for adults typically 60–100 bpm, though fit individuals and athletes can have lower rates. It changes with activity, emotions, and health, rising when active or stressed and slowing when resting or sleeping. A rate over 100 bpm at rest (tachycardia) or below 60 bpm (bradycardia) may need a doctor’s attention, especially with symptoms like dizziness.

Normal Ranges (Resting)

- Adults: 60–100 bpm

- Athletes: Can be as low as 40 bpm or even 37-38 bpm

- Children: Varies by age (e.g., 80-130 bpm for toddlers)

Factors Affecting Heart Rate

- Activity Level: Increases with exercise.

- Emotions: Stress, anxiety, excitement raise it.

- Physical Factors: Fitness, weight, sleep quality, hormones, pregnancy, medications, alcohol, caffeine.

How to Check Your Heart Rate

- Rest: Sit quietly for 5-10 minutes.

- Locate Pulse: Place index and middle fingers on the thumb-side of your wrist or neck.

- Count: Count beats for 10 seconds and multiply by 6, or use a fitness tracker

Tachycardia

Tachycardia is a heart rhythm disorder where the heart beats too fast, typically over 100 beats per minute (bpm) at rest in adults, signaling an electrical problem or normal response to stress, exercise, or underlying conditions like fever, anemia, anxiety, or thyroid issues, causing symptoms like palpitations, dizziness, and shortness of breath, requiring medical evaluation to determine if it’s benign (sinus tachycardia) or a serious arrhythmia needing treatment.

Types of Tachycardia

- Sinus Tachycardia: A normal response to stress, fever, or exercise, where the sinus node fires too quickly.

- Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT): Abnormal signals start above the ventricles, causing sudden rapid heartbeats, often felt as palpitations.

- Ventricular Tachycardia (VT): A dangerous rhythm originating in the heart’s lower chambers, potentially life-threatening.

- Atrial Fibrillation (AFib) & Flutter: Irregular, rapid heartbeats in the upper chambers (atria).

Common Symptoms

Racing heart or palpitations, Dizziness or lightheadedness, Shortness of breath, and Chest pain or discomfort.

Common Causes & Triggers

- Lifestyle: Caffeine, alcohol, stimulants, smoking, stress, lack of sleep.

- Medical Conditions: Fever, anemia, thyroid disease, dehydration, lung disease, sleep apnea, heart disease, high blood pressure.

- Electrical Issues: Faulty heart wiring or triggers in the heart’s chambers.

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is a slower-than-normal heart rate, typically under 60 beats per minute (bpm) in adults at rest, caused by issues with the heart’s electrical system, certain medications, or underlying conditions like sleep apnea or thyroid problems, leading to symptoms like dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and confusion, though highly fit individuals and athletes may have a normal slow rate. Treatment varies by cause, ranging from lifestyle changes to pacemakers, and involves diagnosing the underlying problem with tools like an EKG.

What it is

- A heart rate below 60 bpm, meaning the heart isn’t pumping enough oxygen-rich blood to the body.

- Can be normal for athletes or during sleep, but problematic if it causes symptoms.

Common types

- Sinus Bradycardia: Slowing of the heart’s natural pacemaker (sinus node).

- Heart Block: Electrical signals from the upper to lower heart chambers are blocked.

Causes

- Heart Issues: Heart disease, previous heart attacks, sick sinus syndrome.

- Medications: Beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers.

- Medical Conditions: Thyroid problems, electrolyte imbalances, sleep apnea, inflammation.

- Lifestyle: Intense physical fitness (often normal), aging.

Symptoms (when problematic)

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, fainting.

- Fatigue, weakness.

- Shortness of breath, chest pain.

- Confusion or memory problems.

Diagnosis & Treatment

- Diagnosis: Physical exam, EKG, Holter monitor, sleep study, blood tests.

- Treatment: Addressing the cause (e.g., changing meds, treating sleep apnea) or using a pacemaker for severe cases.

Pulse

A pulse is the rhythmic expansion and contraction of your arteries as your heart pumps blood, felt as a throbbing sensation, most easily checked at the wrist or neck, indicating your heart rate (beats per minute) and rhythm, crucial for assessing cardiovascular health, with normal resting rates for adults typically 60-100 BPM. “Pulse” also refers to a new 2025 Netflix medical drama series and various tech/business platforms.

In Medicine (Heartbeat)

- What it is: The surge of blood pushing through arteries with each heartbeat.

- Where to find it: Wrist (radial artery), neck (carotid), groin, back of knee, top of foot.

- How to check: Place index and middle fingers lightly on the skin; count beats for 15 seconds and multiply by four.

- Normal Rate (Adults): 60-100 beats per minute (BPM) at rest, but varies with fitness and activity.

- What it tells you: Rate, rhythm (regular/irregular), and strength, signaling potential issues like bradycardia (slow) or tachycardia (fast).

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against artery walls, measured as two numbers (systolic over diastolic) in mmHg, with <120/80 mmHg considered normal, while readings of 120-129 systolic and <80 diastolic are elevated, and ≥130/80 mmHg or higher indicates high blood pressure (hypertension). It fluctuates with activity and emotions, but consistently high pressure (hypertension) increases risks for heart attack, stroke, and kidney disease, requiring lifestyle changes like healthy diet, exercise, and stress management, or medication.

Blood Pressure Numbers Explained

- Systolic (Top Number): Pressure when your heart beats (contracts).

- Diastolic (Bottom Number): Pressure when your heart rests between beats.

Blood Pressure Categories (for adults)

- Normal: Less than 120/80 mmHg.

- Elevated: Systolic 120-129 AND diastolic less than 80.

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): 130/80 mmHg or higher.

- Hypotension (Low Blood Pressure): Readings below 90/60 mmHg can sometimes cause issues like dizziness.

Factors Affecting Blood Pressure

- Activity & Body Position: Changes with exercise, stress, and even breathing.

- Lifestyle: Diet (high salt), weight, smoking, alcohol, and stress.

- Health Conditions: Kidney disease, diabetes, sleep apnea.

- Genetics & Age: Family history and older age increase risk.

Hypertension

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, means blood consistently pushes too hard against artery walls, making the heart work harder and risking heart attack, stroke, and kidney disease. Often symptom-free (the “silent killer”), it’s diagnosed by readings of 130/80 mmHg or higher, with causes including lifestyle (diet, lack of exercise, salt, alcohol) and genetics. Treatment involves lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, weight loss) and medications, with goals to lower blood pressure to a target of 130/80 mmHg or less to prevent serious complications.

Symptoms

- Usually none, but severe cases (180/120 mmHg+) can cause: headaches, chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath, nosebleeds, blurred vision, anxiety, nausea, or confusion.

Causes & Risk Factors

- Primary (Essential) Hypertension: Most common, linked to genetics, aging, obesity, high salt/low potassium diet, inactivity, smoking, excess alcohol.

- Secondary Hypertension: Caused by underlying conditions like kidney disease or endocrine disorders.

Types of Hypertension

- Normal: Below 120/80 mmHg.

- Elevated: Systolic (top number) 120-129 mmHg AND diastolic (bottom) <80 mmHg.

- Stage 1 Hypertension: Systolic 130-139 mmHg OR diastolic 80-89 mmHg.

- Stage 2 Hypertension: Systolic 140 mmHg or higher OR diastolic 90 mmHg or higher.

- Hypertensive Crisis: Above 180/120 mmHg; requires emergency care.

Treatment & Management

- Lifestyle Changes: DASH diet (fruits, veg, whole grains), low sodium, regular exercise, weight management, limiting alcohol, quitting smoking, stress reduction.

- Medications: Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, etc., often used in combination.

Hypotension

Hypotension, or low blood pressure, occurs when blood pressure drops below the normal range (typically <90/60 mmHg) and causes symptoms like dizziness, fainting, blurred vision, and fatigue, indicating insufficient blood flow to organs. While often harmless for healthy individuals, it can stem from dehydration, medication, heart problems, or severe infection, and requires medical attention if symptoms are present, as it can lead to shock or organ damage. Specific types include orthostatic (upon standing) and postprandial (after eating) hypotension.

Symptoms

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Fainting (syncope)

- Blurred vision

- Nausea or vomiting

- Fatigue or weakness

- Confusion

- Rapid, shallow breathing

- Fast heartbeat

- Cold, clammy skin

Common Types & Causes

- Orthostatic Hypotension: Sudden drop when standing up; common with dehydration, aging, or bed rest.

- Postprandial Hypotension: Drop after eating; affects older adults more, linked to Parkinson’s.

- Neurally Mediated: Drop after prolonged standing; affects young people/children.

- Severe Hypotension: Can be caused by severe bleeding, dehydration, sepsis, anaphylaxis, or heart issues.

Cleaning, Dressing & Bandaging

Cleaning, dressing, and bandaging wounds involves first washing hands and the wound gently with clean water and mild soap (avoiding harsh agents like peroxide), then applying antibiotic ointment if needed, covering with a sterile, non-stick dressing, and securing it with a bandage that isn’t too tight to allow circulation, changing it daily or when dirty/wet to promote healing. Always wear gloves, use sterile materials where possible, and apply pressure to stop bleeding before covering, ensuring the dressing extends beyond the wound’s edge.

1. Cleaning the Wound

- Wash Hands: Start with soap and water or hand sanitizer, and wear gloves if available.

- Rinse Wound: Gently flush with clean, lukewarm, running water; mild soap can be used around the wound but avoid getting it directly in.

- Avoid Harsh Cleaners: Do not use hydrogen peroxide or alcohol as they can damage tissue and slow healing.

- Pat Dry: Gently pat the skin dry with a clean cloth; don’t rub.

2. Dressing the Wound

- Apply Ointment: Use a thin layer of antibiotic ointment (if no allergies) to help prevent infection.

- Cover: Place a sterile, non-stick dressing over the entire wound.

- Use Proper Materials: Use sterile gauze for cleaning and covering, but avoid cotton wool as fibers stick.

- For Bleeding: If bleeding soaks through, add another dressing on top; don’t remove the first one.

3. Bandaging the Wound

- Secure the Dressing: Wrap the bandage firmly but not too tightly, ensuring it covers the dressing completely.

- Check Circulation: Press on the skin past the bandage; color should return in under 2 seconds. Loosen if it stays pale.

- Secure with Knot: Tie the ends in a reef knot over the dressing to maintain light pressure.

- Change Regularly: Change dressings daily or when wet/dirty to keep the area clean and moist for healing.

Injection Pushing

“Injection pushing” refers to the technique of slowly and steadily pressing the plunger on a syringe to deliver medication into the body, typically after the needle has been inserted into the skin (subcutaneous) or muscle (intramuscular), requiring a firm, quick insertion and then a slow, steady push to administer the drug smoothly, ensuring proper absorption and minimizing discomfort.

Key Steps for Pushing the Medication

- Prepare: Clean the site, let it dry, hold the syringe like a dart, and insert the needle quickly at a 45-90 degree angle.

- Release Skin (for Subcutaneous): If you pinched the skin, release it after the needle is in place.

- Push Slowly: Gently and steadily press the plunger all the way down to inject the medication at a moderate pace.

- Remove Needle: Pull the needle straight out at the same angle it went in.

- Aftercare: Apply pressure with an alcohol wipe (don’t rub) and apply a bandage if needed.

Important Considerations

- Site Rotation: Always rotate injection sites to prevent tissue damage, notes Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center and MedlinePlus.

- Angle: For subcutaneous, use 45-90 degrees; for intramuscular, use a firm, straight 90-degree thrust.

- Disposal: Immediately place used syringes in a puncture-proof sharps container.

Saline Pushing

Saline pushing, or flushing an IV with normal saline, is a nursing technique using short, forceful pushes with breaks (push-pause method) to clear IV lines, prevent clots, maintain patency (keep open), and administer medications safely, often for pediatric patients with difficult access to ensure medications go in correctly and lines stay clear between uses. This technique involves scrubbing the hub, connecting a saline syringe, and injecting saline in a pulsating motion, ensuring proper clamping for different cap types to avoid complications like infiltration or blood clots.

Purpose of Saline Pushing

- Maintain Patency: Keeps the IV line from clotting (occlusion) with blood.

- Before Medication: Flushes the line to ensure the medication enters the bloodstream at the correct rate and doesn’t mix with incompatible fluids, notes this YouTube video.

- After Medication: Pushes remaining medication out of the tubing.

- Between Drugs: Prevents mixing of incompatible medications.

- Pediatrics: Improves first-attempt success for difficult IV access, say studies on ScienceDirect and another study on ScienceDirect.

Inhaler

Inhalers are small, handheld devices that allow you to breathe medicine in through your mouth, directly to your lungs. Types include metered-dose, dry powder and soft mist inhalers. They usually treat asthma and COPD but providers may prescribe them for other conditions.

Nebulizer

A nebulizer is a medical device that turns liquid medicine into a fine mist, allowing it to be inhaled directly into the lungs through a mouthpiece or mask for treating respiratory conditions like asthma, COPD, and cystic fibrosis. It uses compressed air, oxygen, or ultrasonic power to create an aerosol, delivering medication to relax airways, loosen mucus, and ease breathing for 5-10 minutes per treatment. Nebulizers are available in home (plug-in) and portable (battery-operated) models and are prescribed by doctors.

How it works

- Liquid to mist: The device aerosolizes liquid medicine into tiny droplets.

- Inhalation: You breathe in the mist through a connected mask or mouthpiece.

- Direct delivery: The medicine goes straight to the lungs, providing quick relief.

Common uses

- Asthma attacks and flare-ups

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Bronchitis

Types of medication

- Bronchodilators: Relax airway muscles (e.g., Albuterol, Ipratropium).

- Corticosteroids: Reduce inflammation (e.g., Budesonide).

How to use

- Add prescribed liquid medicine to the nebulizer cup.

- Attach the mouthpiece or mask and connect to the machine.

- Turn it on and breathe normally until the mist stops (usually 5-10 mins).

- Rinse your mouth after use, especially with steroids.

- Clean the equipment regularly.

Blood Grouping

Blood grouping (or blood typing) classifies blood based on inherited antigens (A, B, Rh factor) on red blood cells, creating 8 main types (A+, A-, B+, B-, O+, O-, AB+, AB-) crucial for safe blood transfusions to avoid immune reactions, with O- being the universal donor and AB+ the universal receiver. It’s determined by genes from parents, identifying substances (antigens/antibodies) that cause clumping if incompatible.

The Main Blood Groups (ABO System)

- Group A: Has A antigens on red cells, anti-B antibodies in plasma.

- Group B: Has B antigens on red cells, anti-A antibodies in plasma.

- Group AB: Has both A & B antigens, no antibodies.

- Group O: Has no A or B antigens, both anti-A & anti-B antibodies.

Rh Factor (+/-)

- Rh-positive (+): Has the Rh protein (D antigen).

- Rh-negative (-): Lacks the Rh protein.

Compatibility (Transfusions)

- O negative (O-): Universal Donor:, as it lacks A, B, and Rh antigens, so it won’t trigger a reaction in anyone.

- AB positive (AB+): Universal Recipient:, as it has all antigens and no antibodies to react.

- Matching: Blood must match closely (e.g., A+ receives from A+, A-, O+, O-), but O- can be given in emergencies to anyone.

Blood Glucose

Blood glucose, or blood sugar, is the main sugar in your blood, serving as your body’s primary energy source from food, mainly carbs, regulated by insulin from the pancreas; high levels (hyperglycemia) often signal diabetes, where the body struggles with insulin, leading to excess sugar in the blood, while monitoring it helps manage energy needs and prevent complications like heart disease.

What it is

- Energy source: Glucose comes from carbohydrates in food (fruits, grains, pasta) and travels via your blood to cells for energy.

- Hormonal control: The pancreas releases insulin to help cells absorb glucose; without enough insulin or proper use, sugar stays in the blood.

Why it’s important

- Brain function: Your brain and nerves need a constant supply of glucose.

- Metabolic health: Keeping levels stable prevents serious issues like heart, kidney, and eye disease.

Normal vs. high levels (mg/dL)

- Fasting (before meals): 80–130 mg/dL (or < 100 mg/dL for normal).

- 2 hours after a meal: < 180 mg/dL (or < 140 mg/dL for normal).

How to check

- Wash hands, insert a test strip into a glucose meter, prick your finger with a lancet, touch the blood to the strip, and read the result.

Pathology Training Institute in Bangladesh Best Pathology Training Institute in Bangladesh

Pathology Training Institute in Bangladesh Best Pathology Training Institute in Bangladesh